Psychology of Fraud: What is Rationalization?

By Carla Rodriguez | Apr. 25, 2025 | 8 min. read

What You Will Find Below:

- What is Rationalization

- Personality Types

- Spot the Psychological Red Flags

We’ve all heard and maybe said, “It’s not that big of a deal.” Or maybe, “They won’t even notice.” These are the kinds of quiet justifications that are often an overlooked element when someone is committing fraud: rationalization.

Rationalization is the mindset that turns a bad decision into something someone can live with. And the craziest part is most fraudsters don’t see themselves as fraudsters. They’re not sitting in a dark room scheming like cartoon villains. They’re everyday people, pushed by pressure, given opportunity, until finally they find a justification and say “It’s not that big of a deal.”

In today’s blog, we’ll break down one of the most interesting aspects of the intersection between psychology and fraud.

The Psychology of Fraud: Rationalization

Rationalization is one side of what’s called the Fraud Triangle—a framework introduced by criminologist Donald Cressey in the 1950s. It proposes that three elements must be present for fraud to occur:

• Pressure (like debt or financial trouble),

• Opportunity (lack of oversight), and

• Rationalization

Cressey found that most fraud isn’t committed by inherently bad people. It’s not always the hardened criminal or the career con artist. More often, it’s the quiet, everyday people who find a way to justify unethical behavior.

Rationalization is not about plotting – it’s about people preserving their identity as a “good person.” Without that internal narrative, the fraud would feel too jarring, too wrong. But the brain steps in offers a cushion, an excuse, and softens the action.

In this way, rationalization doesn’t just enable fraud—it makes it feel justifiable.

It’s the mental loophole people crawl through when the pressure gets high and the opportunity is there.

Rationalization and The Lies We Tell Ourselves

You might be wondering if you’ve ever rationalized something. Maybe it was simple like canceling a date or staying out late when you had a big meeting the next day. When rationalization is used to make peace with fraudulent activities it may sound like:

• “I’ve paid into this policy for years. It’s only fair I get something back.”

• “I’m tired and don’t want to go. This won’t hurt anyone.”

• “It’s just bending the rules, not breaking them.”

These thoughts allow otherwise honest individuals to quiet their conscience and move forward with fraud. And the scariest part? Essentially, the brain is protecting itself by rewriting the story.

Who’s Most Likely to Rationalize?

You might assume it’s people under the most stress. And sometimes that’s true. But research suggests it’s not only about how bad the pressure it’s about how easy it is to justify the behavior.

In one experiment, participants were more likely to cheat when they believed their actions didn’t directly hurt anyone. The vaguer the harm, the easier it was to lie or inflate the truth.

This is especially important in industries like insurance, where the “victim” is often seen as a faceless, profitable company. If you don’t see a person getting hurt, it’s easier to rationalize a little exaggeration.

To understand who’s most likely to use rationalization to commit a crime, we need to look at the Dark Triad Theory.

The Dark Triad Theory

Fraud isn’t always about financial stress or opportunity, it can also be about personality. Some individuals aren’t just tempted by loopholes, they’re motivated to seek them out. That’s where the Dark Triad comes in.

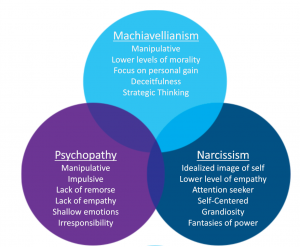

This trio of toxic personality traits, psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism – are used by psychologists to understand people who manipulate, deceive, and exploit others, often without a hint of guilt. Here’s a breakdown of these personality traits – you might remember these from your psychology high school class.

Psychopathy:

Psychopathy is often misunderstood. People tend to think of movie-style villains—violent, dangerous, deranged. But most psychopaths aren’t criminals. In fact, many are intelligent, socially skilled, and can hold down jobs… or file perfectly structured insurance claims.

Psychological traits of psychopathy include:

Low empathy: They struggle to emotionally connect with others. This makes it easier to lie, exploit, or harm without guilt.

High impulsivity: They act quickly, often without planning, based on immediate gratification.

Fearlessness: They’re less sensitive to punishment or risk, which fuels bold actions (like filing a completely fake claim and not blinking when questioned).

In the fraud world, these are the individuals who might inflate a claim or stage an accident on a whim, not because they’re desperate—but because they feel nothing stopping them.

Neurologically, research has shown that psychopaths often have reduced activity in the amygdala (the brain’s emotion center) and weaker connections between the prefrontal cortex and limbic system, which impacts judgment and emotional regulation (Kiehl, 2006), this means they don’t process guilt or consequences like the rest of us.

Machiavellianism:

If psychopathy is impulsive, Machiavellianism is deliberate.

Named after Niccolò Machiavelli, the Renaissance thinker famous for his “the ends justify the means” mentality, Machiavellians are strategic, manipulative, and coldly calculating. They don’t lie on a whim, they lie with purpose and planning.

Psychological traits of Machiavellianism include:

- High self-interest and low empathy

- Long-term strategic thinking

- The belief that morality is relative

In practice, a Machiavellian fraudster might spend weeks building a fake narrative, staging photos, and coordinating with others to create a fraud ring. Their strength isn’t emotion—it’s mental agility and manipulative prowess.

Psychologically, these individuals often score high on the MACH-IV personality scale, which measures traits like cynicism, manipulativeness, and emotional detachment (Christie & Geis, 1970). Studies have shown they’re more likely to justify unethical behavior as “necessary” or “smart,” especially if it leads to personal gain.

They thrive in low-oversight environments, where they can bend rules undetected. This makes them especially dangerous in corporate or team settings, where their charm and intelligence mask deeper manipulation.

Narcissism:

Narcissists aren’t necessarily cold or calculating but they are consumed by the belief that they’re special. They crave recognition, praise, and admiration. And when life doesn’t deliver, they often believe they’re entitled to take what they feel the world owes them.

Psychological traits of narcissism include:

Grandiosity: A belief that they are superior and deserve more than others.

Fragile ego: Despite their confidence, narcissists are highly sensitive to criticism or rejection.

Exploitation: They often manipulate others to serve their self-image or boost their status.

In fraud, narcissists might submit exaggerated claims—not because they need the money, but because they feel wronged, overlooked, or underappreciated. They tell themselves, “I’m not stealing—I’m reclaiming what’s mine.”

Clinically, narcissists often fall under the umbrella of Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), which is linked to inflated self-importance and a lack of empathy. But even those without the diagnosis can show subclinical narcissistic traits that influence their behavior.

What makes narcissists particularly tricky is that they can be charming, persuasive, and even inspiring. But when their ego is bruised or they feel slighted, they’re more likely to bend the truth, or outright fabricate it, to restore their sense of control.

3 Personality Types: psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism

All three lead to fraud but for very different reasons:

- The psychopath doesn’t feel guilt.

- The Machiavellian doesn’t care about morality.

- The narcissist feels above the rules.

Together, these traits form a potent psychological blueprint for manipulative, deceptive, and unethical behavior.

Research from Modic et al. (2018) confirms this: people who score high on any of these traits—especially in combination—are significantly more likely to engage in fraud, from exaggerating insurance claims to corporate embezzlement.

The more you understand these traits, the better you can spot the signs early, build better fraud detection systems, and even design fraud-resistant environments that limit manipulation and emotional blind spots.

The Real Cost of Justifying Fraud

The truth? Rationalization fuels an $80 billion-a-year fraud problem in the U.S. alone (Coalition Against Insurance Fraud). That’s money that impacts premiums and slows claims, and losses across the board.

And here’s where things get real: rationalization is contagious. In workplaces where small infractions are normalized, people start thinking, “Well, if they’re doing it, I can too.” Fraud becomes a culture, not a one-off.

Spotting the Red Flags

Want to stop fraud before it happens? Start by listening—not just for lies, but for the language of rationalization. These subtle cues often signal that someone is beginning to justify unethical behavior:

- “Everyone works the numbers.”

A sign of normalization—they believe dishonest behavior is standard practice. - “I’ve been loyal for years. I deserve this.”

Rooted in entitled thinking. The person is trying to justify actions based on perceived fairness or owed compensation. - “They’ll never notice.”

Phrases like this show a low perceived risk and the belief that the fraud is too small to matter or be caught. - “It’s not really hurting anyone.”

Classic moral minimization. They disconnect their action from its broader impact. - “They can afford it.”

A red flag for displacement of blame—placing the responsibility on the organization instead of the individual. - “It’s not fraud—it’s just bending the rules.”

Watch for reframing—changing the language to reduce guilt or make the act feel less serious. - “I’m just playing the game like everyone else.”

Reveals peer influence and a culture where cutting corners is accepted.

Rationalization might be the quietest part of the fraud triangle, but it’s the most personal. It’s where people rewrite their internal stories to justify what they never thought they’d do. And the more we understand it and can recognize it when others do it, the better we can prevent it.

If you’re in claims, risk, or fraud prevention, watch for the subtle signs it’s not always the big lies.

Click here to browse through our continuing education library and sign up for our Psychology of Fraud webinar.

Sources:

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2020). Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse.

- Modic, D., Palomäki, J., Drosinou, M., & Laakasuo, M. (2018). The Psychology of Insurance Fraud: A Dark Triad Perspective. Journal of Financial Crime.

- Coalition Against Insurance Fraud. (2024). Fraud Statistics. https://insurancefraud.org

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).